| Vol. 10 No. 1 |

April 2004 |

|

| |

|

Umsiedler and Aussiedler by Henry Neufeld. We call them "Umsiedler" but they are really "Aussiedler," these Germanic folk (including Mennonites) who left Russia and other eastern bloc countries to resettle in Germany. "Umsiedler" refers to those who moved from the old East Germany to West Germany. "Aussiedler" describes those who migrate to Germany from former eastern bloc countries This distinction was made by Dr. Heinrich Loewen in a wide ranging lecture to a crowd of 400 at the February Mennonite Historical Society of BC event. Loewen, currently archivist at the Centre of MB Studies in Winnipeg, based his talk on personal experience and on his research. His PhD studies explored the nurturing of young Mennonites in the church. Loewen was born in Kirgizstan where his father was active in the underground church; his father spent eight years in prison. The family moved to Latvia in 1966 and to Germany in 1976. Young Loewen saw his father struggle in the new culture. "My father knew how to survive in a persecution culture, but not (how to survive) in Germany." The question of Christian survival in a non-persecutory environment persisted for Loewen and it was discussions with John B. Toews and Hans Kasdorf in Fresno which helped Loewen find "home". "We (Mennonites) see ourselves as a family," said Loewen, "and the concern I have is that we will lose this biblical aspect of the kingdom, the kingdom of God is a family," he said. Loewen traced the migratory patterns of Mennonites to and from Russia, noting that the persecution and turmoil in the 1914 -1970 era had a traumatic effect on people. The Aussiedler bring this martyred past into their new congregations in Germany. The period from 1970 to the present, when migration from Russia to Germany increased dramatically, is a time of integration. People left the former USSR because of the past traumatic experiences: religious persecution, the desire to live in a German culture and the insecure political and economic climate in Russia. The Russian Mennonites now in Germany don¹t care about politics and are suspicious of anything socialist, said Loewen. The first groups that came to Germany 30 years ago had no difficulty finding work and succeeding economically. More recent arrivals from eastern bloc countries are more highly educated and less likely to find work in their chosen field. They’re also entering a Germany with a high unemployment rate, partly due to German reunification. The early 1970’s Aussiedler were welcomed in Germany. Now, as their numbers increase and unemployment is higher, social problems develop. The older people live in enclaves and some young people, caught in the cultural clash, turn to drugs, alcohol and prostitution. Mennonite churches among the Aussiedler are growing. The conservative groups "which clearly tell people what to do" are growing the fastest, Loewen said. He believes this is a result of years of conditioning in Communist regimes where people were told what to do. These groups, he said, were effective in involving children and youth in church activities. "They learned from the Communists how to work with children," he said. The evening also included a brief account by Rev. Dick Rempel of their five years work with Aussiedler in the 1990’s, music by John and Rita Thiessen, and acknowledgement of MHSBC volunteers by Hugo Friesen. Mennonites and Art Art exhibit by Ray Dirks and other Mennonite artists: 1-5 pm

Annual General Meeting to follow lecture Editorial It is always exciting to introduce new features to our newsletter, especially so when we can welcome new writers as well. In this issue, we will begin a series What’s in a name. The first articles focus on the Hildebrand and Teichrob names. Other names will follow, depending on reader contributions. Researching the Mennonite …in Paraguay” is the start of a new series on the ‘how to’s of genealogical research. The way we were brings us to the community of Black Creek, and another interesting chapter in Mennonite history. Photo gallery will resume next month. If you have photos with unfamiliar faces, other readers may be able to help. Bring them to the centre. Also, we would be glad to publish queries from those looking for relatives. Thank you to all of those who took the time to write and research articles for this newsletter, both to those writing for the first time, and to our regular contributors. It really feels as if the newsletter is starting to pick up momentum! As always, we appreciate your comments on these changes, or any other aspect of our newsletter. Send letters or comments to the MHSBC office, or directly to

Created in the image of God: the art of Ray Dirks

When Ray Dirks and his wife Katie visited Machu Picchu in 1977, he found that, although the ruins lived up to expectation, he was more interested in the people and cultures he crossed in his path. Ever since, his career has had an international focus, one based in the Genesis verse that states we are all created in the image of God. Ray Dirks was born in Abbotsford and educated at MEI, Columbia Bible College and Vancouver Community College. He married Katie Reimer in 1977. Together they took on voluntary positions with MB Missions and Services and moved to Kinshasa, Zaire where Ray was an illustrator for the MB conference. In 1985, they moved to Winnipeg and Ray began to work as a freelance artist and designer - for ChristianWeek and the Mennonite Economic Development Associates. In 1991 Ray began a curatorial career as well. He returned to Africa, a continent he had learned to love passionately, to work with artists to put together exhibitions of contemporary art. The goal was always to bring positive images and messages about Africa to North Americans. Messages, while not denying the terrible tragedies that are all too commonly found in Africa, that focused on the many good and decent people who can readily be found on that great continent. In 1995 Ray brought together the largest exhibition of contemporary African art to ever tour in Canada, Rise with the sun: women and Africa. Its tour included a stop at the Canadian Museum of Civilization. Since1998 Ray has been director of the Mennonite Heritage Centre (MHC) art gallery in Winnipeg, developing it into a professional, full-time gallery where artists are held up as gifted by God. This gallery was established under the conditions that Ray would raise 100% of the budget, which he has succeeded in doing. The gallery has gained a reputation across Canada as a place supporting Christian artists within the church and as a place where artists from the Global South have a home. In 2002 Ray was invited to be artist-in-residence at the Overseas Ministries Study Center and Research Fellow at Yale University. both in New Haven, Connecticut. As a result of his international experience and sensitivity he has also been invited to work with refugee students at a Winnipeg inner city high school.

Ray Dirks will be lecturing on the topic “Mennonites and Art” at the spring event of the Mennonite Historical Society of BC, Saturday May 8, at the Garden Park Tower. Come early to meet the artist and to see his works along with the art of several other local Mennonite artists. Dirk’s book, In God’s Image will be available for purchase. Commandeered by the Red Army: My dear nephew, In 1922, the day before Easter, I came home from an evening of visiting to find a strange wagon on our yard. As I came closer, I saw that it held two men, their hands and feet tied. An armed man, standing nearby, ordered me to hitch up our horses. My father should drive him to a neighbouring Russian village, he said. I told him that this would not work, since my (step)father could not speak Russian. Father was relieved that he did not have to go. At this point, a 12-year-old boy came on our yard, and I asked him if he’d like to come along. Oh yes, he said, he’d like to. So we put straw on our wagon, moved the men (a Russian and a Gypsy) onto it, and started off toward Tomakowka. It was in the dark of night. Once we were out of our village, The armed man became afraid. He told me to stop; I stopped. He spoke to the Russian and said that he wasn’t sure if he was guilty of murder, so if he would promise to report within a week to Tomakowka, then he would release him. If not, he would shoot him the next time he saw him. The Russian crossed himself, promised by all that was sacred, and left. I shall write why these men were prisoners. Not far from where we lived were Russian farmers. At night, bandits had come and had murdered the family, except for this armed man, who had hidden under the horse trough. Later, he thought he recognized two of the bandits who killed his family, so he went to the authorities for permission to find them and bring them to justice. The authorities agreed, and gave him a gun, and he went to the city of Alexandrowsk and searched until he found them. We came to the armed man’s house, and he gave us a bed, and told us to go to sleep. He wanted to go to the church to watch the blessing of the Easter Paska. We asked if we could come along, but he said no, so we fed the horses and went to sleep. Early the next morning-it was Easter Sunday-- he woke us and gave us breakfast. The village was full of Red soldiers; when they saw us and our wagon, they commandeered us to drive for them. There were hundreds of wagons, and soon we found acquaintances from our village among them, who had also been forced to drive. We tried to move our wagon closer to them, and succeeded. My friend Gerhard Elias came to my wagon, but he fell off and the wagon drove over his legs. There was no doctor, so the poor fellow had to suffer. We tried to look after his horses while he lay on the wagon. We were not prepared for such a long trip, so both we and our horses soon suffered from hunger. We stole hay for our horses when we saw haystacks-the Russian farmers did not give us a hard time about it because they didn’t know whether we belonged to the army or not. Before we’d get to a village, a rider would be sent ahead to order the villagers to bake bread and cook meals. We did not get any, so we would try to steal a bread or some buns. One of us would talk very friendly to the watchman while the other did the stealing. It was strange, but I found I got away the best in the stealing of the bread. The breads were very large, and one was enough for us for the evening meal. By the next day, we would be hungry again, and we would repeat the process. One night we slept under a wagon and as I had the chance I was able to grab another loaf and hide it in the barn so we’d have something to eat the next morning. We looked forward to eating this bread, but when we went to get it in the morning, it was gone. We thought we’d be hungry all day, when someone gave us some groats. A Lutheran boy cooked them in the pail we watered the horses in, but when we tried to eat it, Oh, dear, there was so much sand in the porridge that we couldn’t eat it. We could either go hungry or try to steal another loaf of bread. Instead, we went to the poor Russians in the village and begged for food. They gave us some, and it tasted very good. We’d already been away from home for over a week, and would dearly have loved to go home, so we went to the office where the authorities were. They chased us out with a whip. The next morning the General came along. We begged to be released, but he said no. The 12-year-old boy who was with me, jumped up and shouted, ‘You let us go, or I’ll smash you one in the face!’ The General said, “You! I’ll never let you go. You’re coming along to the front!’ But the next day they released us. Now, how to get home. We had no idea where we were, and did not know the way home, but we set out. We came to the place where the front had been; bodies of dead men and horses lay there, wounded horses breathing very heavy. We came to Mennonite villages but they would not give us anything. I think they had nothing left; the war had taken everything. Even the soldiers went hungry. I don’t remember how we got home. Note: The 12-year-old boy had been left behind in our village by a band of Machnowzie. He was an orphan, and had been left by his brothers who were part of a murdering band, German Lutherans. Very few Mennonites were in such bands. Book Review: Journey into Freedom, by Edith Elizabeth

Friesen Whether our ancestors came to Canada in the twenties or the forties, the edges of our lives as children were always full of whispered stories from the past about hunger, terror, pain, death and indescribable loss. For some, these stories are first hand accounts. Edith Friesen has combined both of these by remembering the stories that haunted her childhood, and recording the first-hand accounts of her mother, two aunts and an uncle. The four voices combine to flesh out the stories of freedom lost, freedom sought and freedom regained. Interspersed with the vignettes, told in chronological order beginning with the forced deportation of their father into Stalin’s gulag in 1931, are sections of Mennonite history. These facts are told in such an engaging way, that one is quite eager to read what is made alive in the telling. For those uninitiated into Mennonite history, these sections provide necessary background for the story. For those of us who have been immersed in our history, they tell the story in a picturesque and creative way. Especially gripping were the seven word pictures interspersed throughout the book, beginning with "Imagine this", vividly describing a turning point in the lives of the refugees. Edith begins each chapter with a quote about freedom, the central theme of the book. The quote from Chapter 10: "The aspiration toward freedom is the most essentially human of all human manifestations".......Eric Hoffer, is illustrated over and over in the story Their own aspiration toward freedom is apparent when they are disenfranchised as kulaks and must continue to survive even after their house is taken; when they are fleeing to Germany and trying to make a new life in all the uncertainty; when they must protect themselves from Russian soldiers, when they dream and work towards a new home in Canada. The story is broadened by John's perspective, telling of his experiences as a soldier forcibly drawn into the German army. His courage and resourcefulness as he attempts to find freedom in western Germany, but is arrested by Russians, are illustrated in Chapter Ten: "So I tell the commander: See the guard who brought us in? He and his two other companions have confiscated liquor from the two other fellows with me. After this, they are planning to celebrate. Don't you think it would be a good idea if you would join them and let us go? To my surprise, he agrees. “He tells the sentry to take us to the border. . ..He tells us to sneak through the gap. . .We go and arrive in West Germany". Freedom is the central theme of our Anabaptist heritage as well, when one considers the freedom from Rome’s power sought by Menno Simons; the freedom sought by those Mennonites who came to Prussia, and later Russia; the freedom sought by those doomed by communism’s grip; the freedom quest that gave courage to this family as they emigrated to a strange country across the sea; the freedom in Canada that helped them prosper once more. This book tells a story we thought we knew, in a new and very readable way. We feel that we get to know the mother and four siblings who survived, as real people. This book will surely be enjoyed by a wide audience. It can be purchased at the archives. Molotschna Bicentennial Celebrations, June events by John Konrad June 2-5. 4-day International Conference at the Melitopol State Pedagogical University. Saturday, June 5, 14:30-16:30 - A granite bench will be unveiled at the Lichtenau/Svetlodolinskoe Railway Station from where many Mennonites immigrated to Canada and abroad in the 1920s, including our parents, and were deported to Siberia in the 1930s and 1940s. June 6 - Unveiling and dedication of the Molotschna Bicentennial Settler Monument, in the Zentralschule (main square) in Molochansk (Halbstadt), 11:30am - 12:30pm, commemorating the Bicentennial of the first Mennonite settlement in Molotschna. There will be Ukrainian and Canadian government representatives present. Tuesday morning, June 8, 10:30am - 12:00pm, village of Vladovka/Waldheim, unveiling of Waldheim/Vladovka memorial plaque in memory of the founders of Waldheim Hospital and of the Neufeld plaque of the I.J. Neufeld and Company Farm Implements Factory. Tuesday afternoon, June 8, 15:00 - 16:30, unveiling and dedication of historical Century marker in the cemetery of the village of Gnadenfeld/Bogdanovka Researching the 1930 Mennonite Refugees from Germany to Paraguay

I set about to try and find information on this family and found the following listing on the internet: German Genealogy: Paraguay The source: R 57 "Deutsches Ausland-Institut", Band 4: Karteien includes many items, but in particular 23-29 Kartei der Auswanderung von Russlanddeutschen nach Argentinien, Brasilien, Kanada, Paraguay und Uruguay [Emigration file Cards of Germans from Russia to Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Paraguay and Uruguay] I wrote a letter quoting the above source information (you can also email them ) and enquiring if they had any information on our refugee family members. I gave as much detail regarding names, birthdates and places of birth as possible and included my postal and email addresses. I received an email confirming that they had found the immigration cards and stating that they would mail photocopies to me (at no cost). When I received the photocopies I found they included items such as birthdates, places of birth, wife’s name and maiden name and a list of the children including birthdates. In our case it was surprising to learn that a boy had been born in the refugee camp at Moelln, Germany and that their mother-in-law was also with them. The card also contained the date of departure and the destination as Paraguay. I then contacted several Mennonite archives and was directed to the files of Harold S Bender in the Archives of the Mennonite Church in Goshen Indiana . They have extensive files on this immigration including photographs and ship passenger lists. They charge a fee, which I gladly paid, to have them seek out the passenger lists. They we able to locate the first 4 of the 5 transports which listed approximately 1434 of the 1572 Mennonites who were transported to Paraguay in 1930. The ships and sailing dates are as follows:

On Transport IV I found my grandfathers’ brother’s family and mother-in-law. The lists also gives ages, father’s name for heads of families and the location in Russia from which they originated. These passenger lists are now available on the internet and a copy is also in the MHSBC archives. Hopefully, one day I can get to the archive in Goshen and do further research. I then found that a project had been undertaken by the Fernheim Colony Archives, Filadelfia, Paraguay to index the obituaries that had appeared in the Mennoblatt from 1931 to 2000. This list is now available on the internet as well . While the MHSBC does not have a complete Mennoblatt collection I was able to locate at least one obituary which gave a great deal of further information about this family. The Hiebert Library at Fresno Pacific University has a complete set of the Mennoblatt and I believe copies can be obtained from them if you have the issue number, date and page number which is provided in the on-line index. For possible further information there are two Mennonite archives in Paraguay. They can be contacted as follows: Archivo Colonia Fernheim Archivo Mennonita, Instituto Biblico Asunción There is undoubtedly more to discover but increasingly that which was

beyond the reach of most family historians can now be accessed via email

and the internet. I hope this may be of assistance to others

and I would certainly be grateful for information on any other sources of

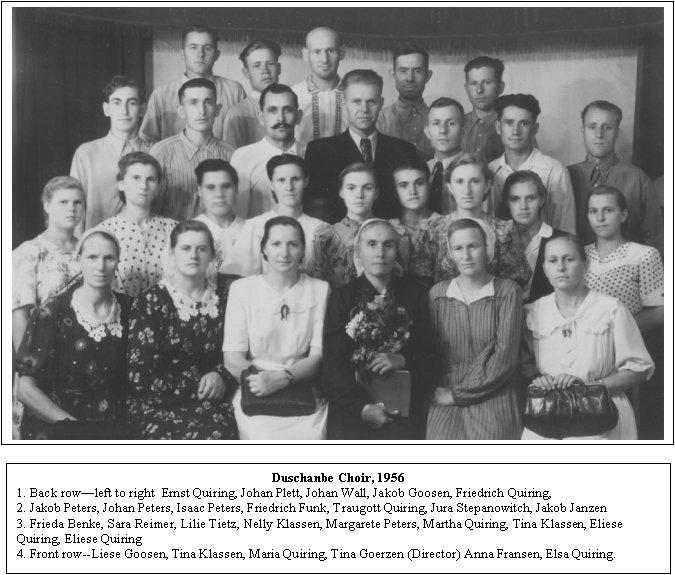

Paraguay family history. Reinländer Gemeinde Buch (Church Register) Many of us that are researching our Mennonite roots are familiar with the Reinländer Gemeinde Buch. This church register of membership was started about 1880 and includes the original families who moved from Russia to Canada. Their origins were in Chortitza and Fuerstenland colonies but the register also includes new families that were formed before 1903 in Canada. A second Register, known as Old Colony B, was started in Manitoba and was continued in the Manitoba Colony in Mexico. It includes families formed by marriage starting in 1903. For those who moved to Mexico the register begins after 1923. A third Register known as Old Colony C, was begun in Mexico in 1921 for all families in the Manitoba Colony. This Register includes all families formed by marriage up to and including 1942. Occasional entries were made after this date for births, baptisms and deaths. The project that I am heading up is the transcribing of the Old Colony C Register. The result will be an extensive document that can be easily used for research in tracing Mennonite ancestry. If you are interested in volunteering for this project you can contact me, Don Fehr, at 604-942-5546 or email don_fehr@telus.net. If you are on the internet and your computer can support Microsoft 2000 I can email you a template and the documents for transcription. Recent Acquisitions 1. Five Microfilms from the Odessa Region State Archives which contain records from the Board of Guardians for Foreign Settlers in the Ukraine. This material has been extracted because it contains information regarding Mennonites. 2. Kroeker Family CD project contains over 600 family photos and 500 documents following movements from Molotschna to Nebraska, Oklahoma and Saskatchewan. Produced and donated by Keith Kroeker. 3. Harder Family Review – 3 binders containing a complete collection of the periodical (issues 1-64) and indexes of titles, articles, features and names (issues 1-20) Donated and produced by Ron Isaak. 4. 1930 Mennonite Refugee Transport from Moelln Germany to Paraguay lists for the SS Bayern, SS General Belgrano, SS Sierra Cordoba and the SS Villagracia. Produced and donated by Ron Isaak. 5. Mennonite Family History – periodical published in Pennsylvania containing interesting stories and family histories. 6. Revision Lists for Schönwiese 1816, 1858. Donated by Tim Janzen. 7. An account of the descendants of Heinrich Fehr and Sarah Neufeld produced and donated by Don Fehr. 8. The life story of Gerhard & Maria Siemens produced and donated by George Siemens. 9. A CD of the Reinländer Gemeinde Buch (1880-1903) and related material donated by Alf Redekop. 10. Steinfeld Memories – 2 videos from a recent Reunion includes Steinfeld History & a Worship Service donated by Gordon & Anne Bell. Family Histories 1. Gerhard G. Derksen Family Book Singing the Lord’s song: the story of Tina Richert Goerzen, choir director of Duschanbe Written by Maria Rogalsky Quiring and translated and edited by Hugo

Friesen A train car load of people, among them Mennonites who were being repatriated from Germany, was on its way back to Russia. As they were crossing the border in overcrowded cattle cars, the wheel bearings of their car suddenly began to smoke. The train stopped at a small station near Brest-Litovsk and the car was pulled aside for repairs while the rest of the train went on a few kilometers before coming to a halt. The people in the damaged car were told to leave the car and soon they were told to take their possessions and carry them the two kilometers to the train. Some people came from the train to help make the transfer as quickly as possible. Among these was Tina Richert Goerzen, also known as Tante Tina, who was a great blessing to us later. While people were still carrying their goods and the smaller children,

they heard the sudden blast of the train locomotives’ whistle and the

train was on the move again with its load of the homeless and their meager

possessions. Those who did not get back to the train on time, were

left behind, and their shouting and wailing was to no avail. Who gives the spirit wings, who will carry me in this land The lament goes on and sends a call through heart and soul in the midst of physical suffering seeking salvation but finding no hope in the godless land. A Servant of God Tina Goerzen was eager to be helpful; People had already noticed this when they were transferring the goods from one train to the other. Everyone called her Tante Tina. Her father had been an Elder in the Mennonite Church and had been taken by the merciless authorities in the early thirties. Her own husband was taken in 1937, a few weeks after their wedding. Tante Tina then took care of her sister-in-law (who had also lost her husband in 1937) with three small children and continued her selfless service to those in need. After her sister-in-law died in a labor camp she went to get the children to stay with her in Duschanbe in 1947. Tante Tina’s Personal Account “It was hard for us to understand when we were unloaded in Warsob on October 22, 1945 that God was showing us his love in this situation and that this was now supposed to be our home. We were very sad but later, on Christmas Eve, we went to sing at a number of families who lived with us in our two-storey house. This brought joy to us and the other exiles. In 1946 we were transferred to Duschanbe. Just before Christmas a number of sisters begged me to practice some songs for Christmas. I agreed but never thought that I would continue to be the leader or that a choir would develop from our little circle. I was a very weak singer and now I was supposed to teach others!” (It must be noted that Tante Tina had the special gifts to do this. During the whole time that she worked as the director she was the one that entered the Ziffern (numbers as notes) in the songs and also taught them to the singers.) Now that she was to organize a choir she felt there must be rules which all must follow. In 1969 these rules included the admonition that singing in the choir was not just an enjoyable activity but a service to God. The names of the first choir members were: Maria, Tina, Liese and Anni (Abram) Klassen, Nelly and Tina Klassen, Marie Rogalsky, Leni, Sara and Anni Reimer, Leni and Frieda Toews. Later the following were added: Anna Fransen, Mika Wall, Johann Wall, Hans Peters, Kolja, Anni and Gretel Baerg, Bernhard Peters, Abram Klassen. From 1946 to 1970 (24 years) Tina continued to work with this choir while caring for her sister-in-law’s three children and working at her full time job carrying mortar at a building site. She was 57 years old in 1967; the next year she organized a Sängerfest for all the German speaking people of the area, including Mennonites, Lutherans and Baptists.. Tante Tina died of cancer in June 1971, the last of her family, all of whom had become victims of the NKWD (secret police). During the time that she directed this choir, she worked with 90 singers, 30 of whom served in song at her funeral.

The way we were: Settling in Black Creek by Ben Stobbe The Mennonite settlement in Yarrow is well documented and was the beginning of a significant exodus of Mennonites from the Canadian prairies to British Columbia. However, a much smaller move of Mennonite families from Saskatchewan and Alberta to Vancouver Island remains relatively unknown. In this article, I will discuss some of the early pioneer experiences of Mennonites moving to Black Creek. Black Creek is a small rural community located in mid Vancouver Island. It is situated in the Comox Valley, 130 kilometers north of Nanaimo. Today it is known as a desirable place to live, offering tremendous four season recreation opportunity with world-class ocean fishing in Georgia Strait, beautiful views of the ocean from Miracle Beach, and deep powder skiing at Mt. Washington. But that is not what pulled some Mennonite families from their disappointing arid prairie homesteads in the mid 1930s. In the early 1930’s the Comox Colonization Society was promoting the agricultural possibilities of 12,000 acres of recently logged land, advertising 100-acre parcels for $5 to $7 an acre. This price compared favorably to recently logged land in Abbotsford which was being auctioned starting at $10 per acre. Henry Schultz was the first to respond to these promotional ads, and in October 1932 he purchased 101 acres. He soon placed ads in “Der Nordwesten”, a prairie German-language newspaper, encouraging other families to buy. Eventually 29 households came as early Mennonite settlers to the Comox Valley. Upon hearing about the cheap land available at Black Creek, one man pedaled his bicycle all the way from Yarrow to investigate. (One suspects he may have been tempted to buy and settle down simply to avoid having to pedal back.) Others coming from the prairies had all their goods including horses shipped to Courtenay by train. Many of the Mennonites moving to Black Creek were recent immigrants to Canada. It has been suggested that some had initially hoped to develop a village concept in Black Creek based on their experiences in Ukraine – a relatively compact and exclusive Mennonite settlement. They came with high hopes. The climate was indeed mild and they expected to have their cattle eating grass outside year-round. They wanted to live off the land. Quickly the families started working together clearing land and building houses and barns. They established garden plots by burning, digging or blasting out the huge fir stumps. They soon realized that the soil offered limited agricultural potential. Henry Schultz’s daughter, Elsie Enns, who arrived as a six year old, recalls the Black Creek area having abundant game such as deer and grouse, and fish were plentiful. Families sold produce from fruit and vegetable stands in nearby Courtenay. Supplies were purchased at the local co-op store operated by Henry and Elizabeth Schultz. Mennonites have often been described as very successful farmers. The local history book “Land of Plenty – A History of the Comox District” (edited by D.E. Isenor et. al.) says that the Mennonites were seen as better farmers than a group of Americans from Portland who had arrived slightly earlier. The Americans had wanted to grow fruit trees but found that the soil did not support this. The challenge for these early families was to find means of earning cash, allowing them to pay off the cost of land and housing. Husbands and young men were drawn to the nearby logging camps for work opportunities. Some logging areas were nearby and men would bike the gravel roads for 10 to 15 miles, work for 10 to 12 hours only to find themselves pedaling against the driving rain, collecting mud everywhere. At least these men could come home. Others left their partially completed houses to their wives and children and moved into logging camps. Camp conditions were described as rough, and for men who had only worked with fellow Mennonites on prairie farms, this rapid assimilation with those having different values and expectations was a challenge to their faith and sense of community. German speaking Mennonites were looked on with suspicion and were viewed as a sect. Many felt discrimination, suggesting that logging bosses would give them the difficult and miserable jobs particularly if they refused to work on Sundays. Eventually these men built a reputation of hard, honest work and logging companies preferred having them in the woods. Logging was and continues to be a high-risk occupation. John Falk, who was born in Black Creek, recalls his father saying that the only way you could get a job in a logging camp was to replace someone who had been injured or killed on the job. A few were more fortunate to find other work such as labouring on a dairy farm. One young man found work as a gardener for a local hospital. He was hired in 1936 and worked 10-hour days, 6 days a week, for $80 a month. Of this, $50 was deducted for room and board. These are some of the early pioneer experiences. In a subsequent article I will review the establishment and development of the Mennonite Churches in Black Creek, for it was in these local congregations that Mennonites found social fellowship and spiritual faith. WHAT’S IN A NAME? by Henry Teichrob Every person needs an identity. That is why so many are doing genealogical research. Our first one is received when we are born. We are given a name. Our family name connects us to our ancestors and places us into a family tree. Nationality, ethnicity and family relationships are inherent in it. This identifies us in the larger picture of life. It show that we are rooted in the human family. The study of surnames can be most interesting. Not all societies have considered family names very important. In Western Europe family names became important when rulers listed their citizens for taxation purposes. William the Conqueror did this for the Doomsday Book. In advanced ancient times the use of family names seems rare. Probably few of us know the family names of Aristotle, Cleopatra, Nebuchadnezzar, Seneca or Augustine. Recent historical figures like Winston Churchill, John Dalton, William Carey, Francis Drake, William Shakespeare, Christopher Columbus and Martin Luther used both names. In Christendom, especially in Northern Europe the common use of family names seems to parallel the rise of nationalism. From the Middles Ages we know of Leaf the Lucky, Eric the Red and later of Ivan the Terrible. Napoleon Bonaparte insisted on the use of family names in his day. It seems that in Northern Europe several naming patterns were used.

Occupations like baker, butcher, carpenter, cooper, hunter, miller,

plumber, smith, tanner, tailor, wagoner and many others became family

names. Physical or personal characteristics like long, short, swift,

stout, sweet, strong, etc. all became family names. Some used colors like

green, brown, black, white and gray. When my parents with six children first arrived at Indian Head, Saskatchewan after almost five years of migration from Siberia via Mexico to Canada they started farming in a district completely populated by people whose roots were in Great Britain. They had easy names like Clarke, Gray, Smith, Green, Stewart, Sweet, Woods, Hubbs, Nichols, Page and Prior. A Mennonite name like Teichrob was a real oddity. My parents, unable to speak English and using plattdietch in their home could not carry on conversations with their neighbors. The children with some quickly learned words had to translate as best they could. We were a curiosity. People wanted to know our ethnicity. In the early days of the Great Depression political correctness was measured in British terms and multiculturalism had not yet been invented. We were hard-pressed to explain that we were not Russian nor true Germans but Mennonites. No one in our district had ever heard of such a people. Furthermore our foods like vareneki, schnetki and borscht were really strange. The school children from young to old found it a great sport to say our name in every conceivable fashion. Little wonder that as children we soon asked our parents if we could change our name. Maybe Taylor or Roberts would be so much better. That way our identity would seem to be rooted in the United Kingdom too. I am glad this never happened. Today much genealogical material and the internet allow for good research. Russian Mennonites can easily trace their migration from the Danzig (Gdansk) region. The Registration ordered by Fredrick the Great (der Alte Fritz) in 1772 and completed in 1776, sometimes called a Consignation is readily available. Research beyond that registry can be difficult. Some call that registry a firewall – almost impenetrable. In that listing the name Teichrob is rare; only three or four families carry this name. Germanization was still often resisted by the largely Dutch Mennonite people of the lower Vistula. The spelling of the name shows that while one family used the Germanized form of Teichgref, another family used the Dutch form of Dueckgrave. Folklore handed to my father by his grandfather gave us as children some pride in our name. I cannot vouch for the accuracy of the folklore but it pleased us. He told us that some generations ago our name was Dyck and the reason for the added syllable was the awarding of the title of Count (Graf). This was brought about by the bravery of an ancestor who rescued a princess of the royal family from drowning after slipping down a dike. Of course in Napoleon’s rule of Danzig (1806 – 1812) any evidence of aristocracy was dangerous. Knowledge of the guillotine had spread throughout Europe. Obscuring all aristocratic symbols was expedient. Some records show that the second syllable of the name was changed to a variety of spelling such as grob, grow, krow, krew, roeb, rob and a number of others. In Mennonite village records all of these versions can be found even when the same branch of the family moved or joined a new village. Today many telephone directories list this family name in a variety of spellings. Regardless of the way the name is spelled today (from Teichgraef to Teichrib or Teichrow) those Mennonites who came from Danzig or Russia have a common ancestry dating back to Johann, Abraham, Michael and Peter who are listed in the 1776 Registry. Apparently they were in the landless class working as weavers and tailors in the Village of Krebsfelde just east of Marienburg. Johann, Abraham and Peter joined the first 228 families in 1789 to go to Russia. Johann and Abraham settled in the village of Schönhorst and Peter in the village of Neuenburg. Both villages were in the Chortitza Colony. It seems that Johann and Abraham both died within a decade of their arrival in Russia, Johann, who was married several times left several sons and daughters but Abraham apparently left only two daughters. Peter lived in Neuenburg for a long time and left male offspring. For some reason or other some census taker in Chortitza spelled the name Theichroeb. This spelling appears in a number of records. Johann it seems used both the Teichroeb and the Teichgref versions. Besides Johann, Abraham and Peter the other member of the family was

Michael who apparently was married three times and had eleven children.

Research also indicates that the name Dyck was a Flemish name. Church records show that the Teichgref family in the Danzig region all belonged to the Flemish Church. Since they were weavers and tailors it is probably safe to assume that they came from Flanders which was the heart of the early textile industry in Europe. As children we often wondered if all the teasing and mispronunciation of the name could have been avoided if an ancient ancestor had not been so courageous. Then our name would have remained Dyck which almost has an Anglo-Saxon ring. But perhaps the princess would have lost her life. As a proud Canadian, now a senior, I’m glad that he rescued her and since by now the name has been spread throughout much of Canada, I along with all the other Teichrobs are probably quite content with it regardless of how it is spelled or pronounced. Note: Mennonite Historical Societies in Canada and the USA have much

valuable information about family names and the migration of the

Mennonites. They are most helpful in  Guten Appetit! Guten Appetit!

The following was published in a recent edition of the Heidehof

Information Newsletter: 1. The Japanese eat very little fat and suffer fewer heart attacks than the British or Americans. 2. The Mexicans eat a lot of fat and also suffer fewer heart attacks than British or Americans. 3. The Japanese drink very little red wine and suffer fewer heart attacks that the British or Americans. 4. The Italians and the French drink excessive amounts of red wine and also suffer fewer heart attacks than the British or the Americans. 5. The Germans drink a lot of beer and eat lots of sausage and fats and suffer fewer heart attacks than the British or the Americans. Conclusion: Eat and drink what you like. Speaking English is what kills you.

Hildebrand “A name for Warrior Heroes in mythology and pacifist Mennonites” The name originated in central Europe, probably in a Germanic tribe named the Langobardi, (Long Beards) among whom names ending in ‘brand‘ were common. The Langobardi first appeared in history on the lower reaches of the Elbe River in the area of the present day city of Hamburg. In 300-400AD they migrated south to present day Bavaria-Austria. In 568AD the Langobardi invaded Italy, defeated its Ostrogoth rulers, sacked Rome and then established their own kingdom along the Po river in northern Italy, or present day Lombardy (Langobardi became Lombards) This independent kingdom was maintained until 774AD when it was conquered by Charlemagne (German -Karl der Grosse) and incorporated in the Holy Roman Empire. A famous king of the Langobardi was Liutbrand who reigned from 712 to 744AD. He was the son of Ansbrand and Theodora and had a brother name Sigibrand, who had three sons named Gregor, Ansbrand and Hildebrand. It was probably at this court that the minstrel ballad , “Das Hildebrand Lied” was first sung. (note all the names ending in ‘brand’) “Das Hildebrand Lied” is the oldest surviving manuscript of German epic or heroic poetry. It was written by monks in the monastery of St. Boniface in Fulda, Germany ca, 800 AD. But its origin as a minstrel ballad is at least 100 years earlier. It ranks in antiquity and historical significance with the Beowulf poems in the English language. The original manuscript is now at the Landesbibliothek (State Library) in Kassel, Germany. It disappeared for a while after WW11, but has since been recovered. The second page was found in Los Angeles in 1950, and the first page in Philadelphia in 1972. The ballad tells the story of a mighty warrior named Hildebrand in the

army of Theodoric 11 (‘the great’), King of the Ostrogoths (Eastern

Goths). Hildebrand was a Langobard name, not Gothic, but since Theodoric

(Dietrich von Bern, in German) was born in Vienna in 454AD, both tribes

lived in the same area at that time and Hildebrand could have been in

Theodoric’s army in fact as well as fiction. In 487AD Theodoric embarked on a major campaign to the East and called

on his veterans to follow. When his King called, Hildebrand

deserted his wife and young son to their fate in order to follow his

master. In 493 AD Theodoric turned west to attack his old enemy Odoacer, the King of the Visigoths, now ruling Rome and the Western Roman Empire. According to the ballad the two armies meet in the field, but instead of a massive battle with its attendant slaughter, they agree to settle the conflict in single combat by champions nominated by the respective leaders. Theodoric’s champion is naturally the proven veteran Hildebrand. Odacer chooses Hadubrand, who unknown to all is Hildebrand’s long abandoned son. During the battle Hildebrand recognizes his son and reveals himself as the father. This only heightens Hadubrand’s fury and long festering hatred, fueled by the many years of abandonment, erupts beyond control. As the stronger, more experienced warrior, Hildebrand prevails and has Hadubrand at his mercy. He is prepared to walk away and spare his son’s life. However, Hadubrand’s hatred is so great that even when offered mercy, he treacherously strikes at his father, leaving the latter no option but to kill his son. The father must now live with the knowledge that he has killed his son. This synopsis is based on several scholarly studies of this poem. As you will note from the copies below, it is not a task for amateurs. A poem by Matthew Arnold called “Sohrab and Rustom” deals with this theme and may have been based on Das Hildebrand Lied. In the year 1073 AD, another Hildebrand became famous. Pope Gregory V11 was formerly a priest named Hildebrand from northern Italy. After many years as Priest, Bishop, and Cardinal, he was elected Pope of the Roman Catholic Church in 1073AD and chose the title Gregory V11, after an old mentor. In his epic struggles with temporal rulers of the day, particularly the Holy Roman Emperor Henry 1V, Gregory defined the boundaries of the Church’s spiritual authority. He was later canonized by the Catholic Church. Visitors to Europe may recognize the name of Johan Lucas von Hildebrand. He was an Austrian Army engineer who later built many famous baroque palaces, including Belvedere in Vienna for Prince Eugene of Savoy and The Residenz for the Prince Archbishop of Wurzburg. The first Anabaptist reference to a Hildebrand occurred in the mid 1500’s when Emperor Charles V was sovereign in the Netherlands. As a devout Catholic, Charles was determined to rid his lands of “diese verdammte Wiedertaeufer”. (these damnable Anabaptists) Horst Penner writes, “they fled to the East and safety,” listing a “Hiltibrant” along with others. Over the next several centuries numerous Hildebrands congregated in the general vicinity of Danzig in West Prussia. Some may have been descendents of the Netherlands’ refugee, but it is also likely that many came from elsewhere in central Europe where the name is not uncommon. Some of them became Mennonites, but not all. I will mention only two. The first is a young Lutheran named Peter Hildebrand of Bohnsack, who heard of Catherine the Great’s offer, and was excited by the prospect of owning land, something impossible for him in Prussia. He emigrated to Russia with the first Mennonite migration in 1789 and became baptized into the Mennonite faith in 1791. Two years later he married Helene Höppner, daughter of Jakob Höppner (one of the original deputies); their descendents became the prominent Hildebrand clan in the Chortitza colony. The second is a Heinrich Hildebrand, born 1752, who emigrated to Russia in 1803 from the village of Kleine Wickerau, near the city of Elbing in West Prussia. Heinrich, together with wife Cornelia, stepsons Peter and Jacob Neumann, and sons, Heinrich, Isaac and Dietrich, moved to the village of Muensterberg, Molotschna Colony. There he was allocated a full farm of 66 desiatin with a homestead. He was the writer’s great, great, great grandfather. Hildebrand’s Lied Transcription of first paragraph in old German: Ik gihorta dat seggen dat sih urhettun ænon muo Translation into modern German: Ich hörte das sagen, daß sich Herausfordrer allein

There are 38,000 Mennonites living in Bolivia, in 38 colonies.

MCC has been active in the colonies for the past 43 years.

Carlos Zacharias of MCC took us to visit one of these colonies on our

visit to Bolivia in 2002. The older women were very inquisitive when

they saw me, and the questions were straightforward: Wofähl joa hast

du? (How many years to you have?) Wofähl tjina? (How many

children?) Send ji von Kaunaudau? (Are you from Canada?)

And my favourite: Waunt es dien Maun-de junga ouda de aula? (Which is your

man, the young one or the old one?) by Louise Bergen Price |

In 2001, Ray began to travel the world bringing together an

exhibition of daily life photographs and art from 17 countries entitled In

God's Image: A Global Anabaptist Family for the Mennonite World

Conference. He stayed with ordinary church member families in each

country, documenting their daily lives in words and photographs. At the

same time he met with and commissioned artists. The resulting exhibition

opened at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo in July 2003. It is

currently touring Europe and will come to North America in 2005. Ray also

wrote, designed and did the photography for an accompanying coffee table

book.

In 2001, Ray began to travel the world bringing together an

exhibition of daily life photographs and art from 17 countries entitled In

God's Image: A Global Anabaptist Family for the Mennonite World

Conference. He stayed with ordinary church member families in each

country, documenting their daily lives in words and photographs. At the

same time he met with and commissioned artists. The resulting exhibition

opened at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo in July 2003. It is

currently touring Europe and will come to North America in 2005. Ray also

wrote, designed and did the photography for an accompanying coffee table

book.

Oma’s Easter Paska

Oma’s Easter Paska